Selection of sarbecovirus strains for immunization

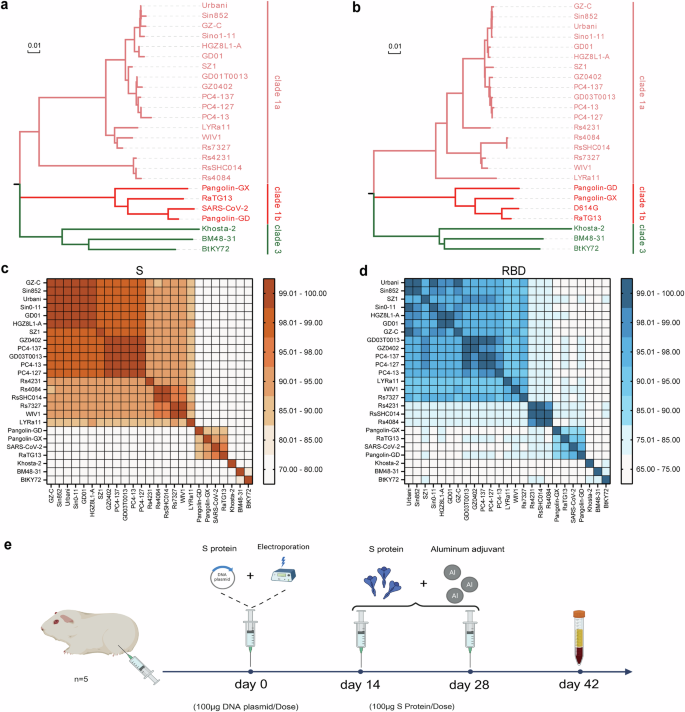

This study assessed the cross-neutralization activity of sarbecoviruses via a pseudovirus neutralization assay. The initial strain selection was guided by the phylogenetic framework established by Starr et al.16, which comprehensively delineated the known ACE2-utilizing sarbecoviruses (Supplementary Fig. 1). Because the cellular receptor for clade 2 viruses remains unidentified and no suitable titration cell lines are available, clade 2 members were excluded from this analysis. To ensure broad phylogenetic and host diversity while maintaining experimental feasibility, we selected 25 representative sarbecoviruses from clades 1a, 1b, and 3. The selection encompassed strains that cover distinct phylogenetic sublineages within each ACE2-using clade and differ in host species (bats, civets, pangolins, and humans). Phylogenetic trees were subsequently constructed on the basis of the amino acid sequences of the full-length S protein and its RBD for these selected viruses (Fig. 1a and b). The topologies inferred from the S- and RBD-based trees were largely concordant, although subtle differences were observed within clade 1a and, more prominently, among clade 1b viruses. In particular, several clade 1b strains (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, RaTG13, and PCoV-GD) presented relatively shifted positions between the two trees, suggesting that distinct evolutionary pressures act on the RBD region. The amino acid identities of the S proteins between SARS-CoV and SARS-like coronaviruses in clade 1a exceeded 87.4% (Fig. 1c), whereas the RBD identity was greater than 80.7% (Fig. 1d). The S protein sequence identities between clade 1a and clades 1b and 3 ranged from 75.7 to 78.0% and from 72.6 to 76.0%, respectively (Fig. 1c). The corresponding RBD identities were 72.6–77.6% and 69.0–75.3%, respectively (Fig. 1d). In clades 1b and 3, the S protein sequence identities ranged from 71.4 to 72.3%, and the RBD identities ranged from 66.4 to 73.5%. Notably, S protein sequence identities were consistently greater than those of the RBD. Among clade 1b strains, the full-length amino acid sequence identities of S proteins between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 and between SARS-CoV-2 and PCoV-GD were 97.3% and 89.9%, respectively; the RBD amino acid sequence identities were 90.1% and 96.9%, respectively (Fig. 1c and d). These results indicate that SARS-CoV-2 shares greater overall S protein similarity with RaTG13 than with PCoV-GD does, although its RBD is more similar to that of PCoV-GD than to that of RaTG13.

Selection and analysis of 25 sarbecovirus immunogens. a, b Phylogenetic trees of sarbecovirus S proteins and RBD regions constructed from amino acid sequences. c, d Heatmaps showing the amino acid sequence identities of the Sarbecovirus S proteins and RBD regions. e Immunization protocol diagram. Guinea pigs were immunized following a DNA prime–protein boost regimen. The initial DNA immunization (100 μg of spike-encoding plasmid DNA) was delivered via intramuscular injection followed by electroporation. Two booster doses containing 100 μg of the corresponding purified S protein formulated with an equal volume of aluminum adjuvant were administered at 14-day intervals after priming. Blood samples were collected 14 days after the third immunization for serum preparation

To investigate the antigenic clustering of immune responses among various sarbecovirus lineages, we immunized guinea pigs with the spike (S) proteins of 25 representative sarbecovirus strains. A DNA prime–protein boost regimen was used, as this heterologous immunization strategy has been shown to enhance both germinal center formation and affinity maturation, resulting in stronger and broader neutralizing antibody responses than homologous immunization schemes.17,18,19,20,21,22 The initial immunization consisted of plasmids encoding the full-length S protein DNA, which was administered intramuscularly followed by electroporation to increase DNA uptake, followed by two booster immunizations with the corresponding purified S proteins formulated with an aluminum adjuvant on days 14 and 28 after priming. Serum samples were collected two weeks after the third immunization for cross-neutralization analysis (Fig. 1e). To ensure comparability among immunogens, all 25 Sarbecovirus S DNA plasmids were confirmed to exhibit comparable in vitro expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 2). The corresponding purified S proteins used for booster immunizations exhibited greater than 95% purity (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Comparison of the cross-neutralization reactivity of guinea pig sera monovalently immunized with pseudoviruses from 25 sarbecovirus strains

We evaluated the cross-neutralizing activity of guinea pig sera against 24 sarbecovirus pseudoviruses (excluding BM48-31, which lacks receptor usage). Because sarbecoviruses differ substantially in their utilization of TMPRSS2 and other host proteases for cell entry,23,24 pseudovirus neutralization assays were performed using 293T-hACE2 cells to maintain assay consistency and ensure cross-lineage comparability.

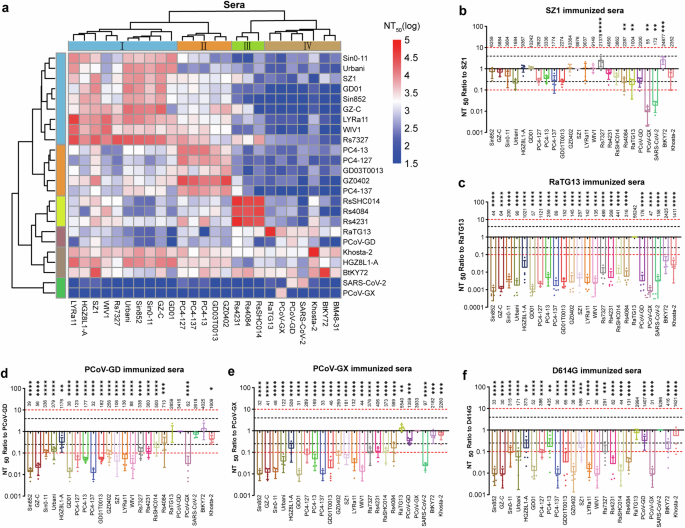

We analyzed the immunogenic relationships among sarbecoviruses via an antigenic cartography-based approach, in which immunogenic relationships were defined as cross-neutralization patterns among immune sera and antigenic relationships were represented as quantitative distances derived from pseudovirus neutralization assays. By comparing logarithmic NT50 values, we determined the antigenic distances between serum–virus pairs. To objectively define group boundaries, Ward’s hierarchical clustering was applied to the antigenic distance matrix, revealing four major clusters (Fig. 2a).

Cross-neutralization analysis of sera from guinea pigs immunized with a monovalent DNA prime and two doses of spike protein corresponding to 25 different sarbecoviruses, tested against pseudoviruses from 24 sarbecovirus strains. a Clustered heatmap of log-transformed NT50 values from cross-neutralization assays of guinea pig sera against 24 sarbecovirus pseudoviruses. The values represent the mean titers from five animals per immunogen group; both axes are hierarchically clustered to depict immunogenic and antigenic relationships. b–f The x-axis shows the sarbecovirus pseudovirus strains, and the y-axis shows the NT50 values relative to those of the immunogen-matched strains. The black and red dashed lines denote 4-fold and 10-fold differences, respectively. Each dot represents one guinea pig (the mean of three technical replicates; n = 5 per group). The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test were used for statistical analysis. Significant differences compared with the homologous immunization group are indicated by asterisks

Cluster I includes SARS-CoV-1 strains (Sin852, GZ-C, Sino1-11, Urbani, HGZ8L1-A, and GD01) along with three bat coronaviruses (LYRa11, WIV1, and Rs7327). Cluster II consists of PC4-127, PC4-13, PC4-137, GD03T0013, and GZ0402. Cluster III includes Rs4231, RsSHC014, and Rs4084. Notably, evolutionary clades 1b (SARS-CoV-2, PCoV-GD, PCoV-GX, and RaTG13) and 3 (BM48-31, BtKY72, and Khosta-2) exhibited similar antigenic and immunogenic profiles and were thus grouped into a single cluster (Cluster IV).

In clade 1a, SZ1 stood out as the broadest immunogen, effectively neutralizing all clade 1a pseudoviruses with only modest reductions in titer (Fig. 2b). Other SARS-CoV-1 strains and related bat or civet strains segregated into two additional groups, which is consistent with distinct antigenic relationships despite close sequence similarity (Supplementary Fig. 4a–q).

Within clade 1b, RaTG13 induced potent autologous responses but showed little cross-neutralization, whereas sera from SARS-CoV-2 D614G, PCoV-GD, and PCoV-GX demonstrated broader activity across clade 1b, although with moderate reductions in titer (Fig. 2c–f). To further dissect homologous and cross-neutralization patterns within clade 1b, we compared reciprocal pseudovirus neutralization among RaTG13, PCoV-GD, PCoV-GX, and SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d). RaTG13 sera showed strong homologous neutralization (NT₅₀ ≈ 5.6 × 10⁴) but weak or undetectable activity against SARS-CoV-2 and PCoV strains, with >40-fold reductions. Conversely, sera raised against SARS-CoV-2 or PCoV strains partially neutralized RaTG13 (NT₅₀ ≈ 3 × 10³–5 × 10³), indicating asymmetric cross-reactivity within clade 1b. These findings support the distinct antigenic position of RaTG13 and highlight the directional nature of antibody cross-recognition among sarbecoviruses.

Two clade 3 sarbecoviruses, BtKY72 and Khosta-2, presented extremely low or undetectable entry efficiency in human ACE2-expressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 6a). To obtain measurable and biologically interpretable neutralization readouts, pseudovirus assays for these two strains were performed using the ACE2 orthologs that each virus can efficiently utilize (Rhinolophus affinis ACE2 for BtKY72 and rabbit ACE2 for Khosta-2).

Importantly, this choice was made solely for methodological consistency rather than to imply natural host receptor usage. Previous studies have shown that the ACE2 compatibility of sarbecoviruses often does not correlate with the host species from which the viruses were isolated and that cross-species receptor usage is highly heterogeneous across subgenera.16,25,26 Using permissive ACE2 orthologs ensures accurate NT₅₀ determination for strains with extremely poor entry through human ACE2, enabling a valid comparison across the full pseudovirus panel. The immune sera from BtKY72, Khosta-2, and other strains strongly cross-neutralized each other (NT50 ≥ 3000) (Supplementary Fig. 6b–d). Surprisingly, sera raised against many clade 1 immunogens also neutralized clade 3 pseudoviruses, revealing unanticipated cross-clade antigenic relationships.

Collectively, these findings highlight the antigenic heterogeneity within clades 1a and 1b, the broad neutralizing capacity of SZ1, and the unexpected cross-reactivity between clade 1 and clade 3 sarbecoviruses.

Amino acid residues affecting sarbecovirus antigenicity

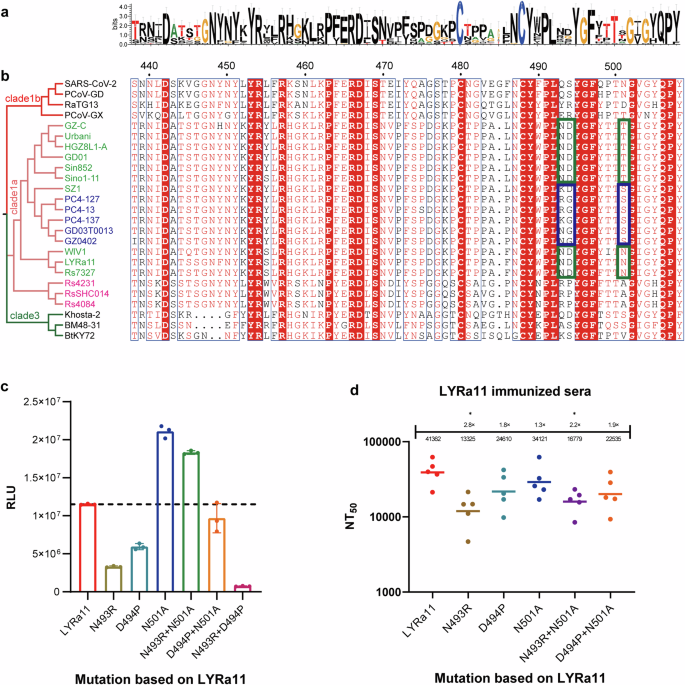

The RBD is the primary target of sarbecovirus neutralization, with major sequence variations concentrated in the receptor-binding motif (RBM). To explore whether specific amino acid residues shape antigenic properties, we compared RBM sequences and antigenic profiles across clade 1a viruses (Fig. 3a and b). Rs4231, RsSHC014, and Rs4084 share only 52% RBM amino acid identity with other clade 1a viruses, corresponding to their distinct antigenic profiles. In contrast, although PC4-127, PC4-13, PC4-137, GD03T0013, and GZ0402 display high overall RBD identity (91–93%) with Sin852, GZ-C, Sino1-11, Urbani, HGZ8L1-A, and GD01, their RBM identity (91–93%) is slightly lower than that of LYRa11, WIV1, and Rs7327 (93–94%) (Figs. 1d, 3b). These comparisons indicate that positions 493, 494, and 501 represent major sites of divergence within the RBM.

Analysis of amino acid residues affecting sarbecovirus antigenicity. a Sequence conservation of the RBM region among 25 sarbecoviruses. The number of SARS-CoV-2 residues is indicated. b Phylogenetic tree constructed from the RBD amino acid sequences of 25 sarbecoviruses, along with multiple sequence alignments of RBM regions. Different phylogenetic clades are highlighted in distinct colors. Strains with similar antigenic profiles are shown in the same color, and RBM sequence regions associated with antigenicity are boxed in corresponding colors. c LYRa11 was selected as a representative strain; its spike protein residues at positions 493, 494, and 501 were individually or doubly mutated to the corresponding amino acids in RsSHC014. Pseudovirus titration was performed using these LYRa11 mutants. d Pseudovirus neutralization assays using LYRa11 immune sera against wild-type LYRa11 and its mutants. Each dot represents the NT50 value of an individual guinea pig serum sample. The data are presented as the means of three independent experiments. The bars indicate the means ± standard deviations

We selected LYRa11 as the template for mutagenesis because it is closely related to WIV1 and Rs7327—sharing 93–94% RBM amino acid identity—but differs at key residues (493, 494, and 501), making it an ideal representative background for probing the functional effects of these substitutions. Single- and double-point mutations were introduced at the corresponding positions, replacing the LYRa11 residues with those present in RsSHC014, which exhibits distinct antigenicity. Mutant pseudoviruses were successfully constructed and titrated to equivalent concentrations for infectivity and neutralization assays. Infectivity testing in 293T-ACE2 cells revealed that most mutants presented reduced entry efficiency relative to that of wild-type LYRa11, with the N493R + D494P mutant completely losing infectivity—likely due to structural instability or impaired ACE2 binding (Fig. 3c). Neutralization assays further demonstrated that while most mutants retained pseudovirus neutralization titers similar to those of wild-type LYRa11, the N493R single mutant and N493R + N501A double mutant partially escaped neutralization (2–3-fold reduction), highlighting the role of these residues in modulating antigenicity (Fig. 3d).

Immunogenic relationships among sarbecoviruses

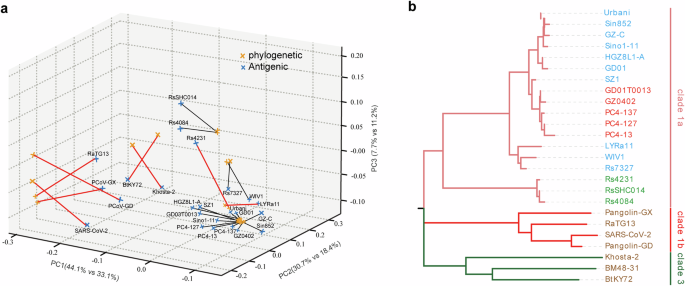

We then performed three-dimensional PCoA on both the antigenic and phylogenetic distance matrices (Supplementary Fig. 7). To directly compare sequence-based relatedness with empirically measured antigenic relationships, we aligned the 3D PCoA embeddings of the two matrices via Procrustes analysis (Fig. 4a). This analysis indicated moderate but significant global concordance (Mantel r = 0.685, p < 0.001; Procrustes r = 0.679) while also revealing a measurable mismatch between the two spaces (disparity = 0.539). Many clade 1a viruses formed similar neighborhoods in both maps, which is consistent with their broadly concordant cross-neutralization patterns. In contrast, eight strains—including RaTG13, BtKY72, Khosta-2, and Rs4231—showed particularly large displacements, highlighting cases where genetic relatedness fails to predict antigenic similarity (Fig. 4b).

Immunogenic relationships among sarbecoviruses. a Phylogenetic and antigenic distance matrices were independently subjected to principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and subsequently aligned via Procrustes transformation. The blue and red points denote phylogenetic and antigenic coordinates, respectively, with lines connecting paired positions of the same strain. The black lines indicate general concordance, whereas the eight strains with the largest displacements are highlighted with bold red lines and labels, representing viruses for which genetic relatedness and antigenic similarity diverge most strongly. b Comparison of RBD amino acid sequence phylogenetic relationships with immunogenic relationships. Strains with similar immunogenicity are shown in the same color

Together, these analyses clarify that antigenic clustering broadly aligns with phylogenetic relationships but also reveals nonlinear divergences driven by functional variations within the RBD. A quantitative comparison between the two spaces further demonstrated that empirical antigenic mapping provides a more functionally relevant and experimentally validated framework for immunogen selection.

Whereas phylogenetic grouping would require at least four representative strains to achieve partial lineage coverage—with residual gaps within clade 1b—the antigenic clustering derived from cross-neutralization data indicates that a minimal trivalent combination (SARS-CoV-1 SZ1, PCoV-GD, and SARS-CoV-2) achieves complete cross-neutralization across all 25 tested sarbecoviruses.

This outcome highlights the practical value of antigenic cartography in guiding parsimonious yet broadly protective vaccine design and provides a data-driven rationale for selecting the trivalent immunogen combination evaluated in subsequent experiments.

Cross-neutralization reactivity between trivalent immunized guinea pig sera and sarbecoviruses

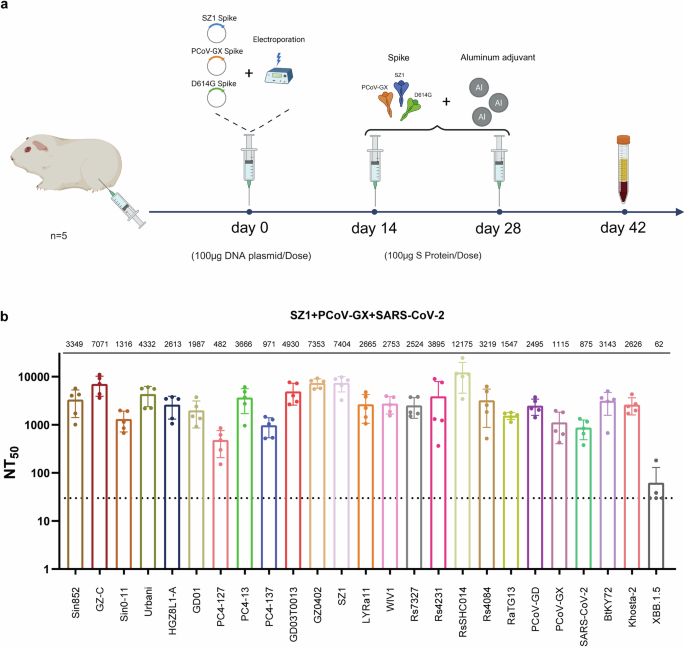

Because monovalent immunogens are unable to neutralize all 25 selected sarbecovirus strains and current pansarbecovirus vaccine development strategies rely primarily on multivalent formulations, we selected three immunogens—SARS-CoV-1 SZ1, SARS-CoV-2 D614G, and PCoV-GX—on the basis of the cross-neutralization results of monovalent immunization. Using a sequential immunization strategy that consisted of priming with spike protein DNA followed by protein boosters, guinea pigs received three doses; sera were collected 2 weeks after the final immunization (Fig. 5a). The collected sera were subjected to cross-neutralization assays against all 25 pseudovirus strains. The results demonstrated that sera from guinea pigs immunized with the trivalent vaccine exhibited broad-spectrum neutralizing activity (Fig. 5b). However, the trivalent immune sera did not neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 XBB.1.5 variant, which is consistent with expectations. This lack of neutralization is likely attributable to the substantial evolutionary distance between SARS-CoV-2 XBB variants and the D614G immunogen, as well as multiple mutations within the RBD that confer immune escape. These findings underscore the importance of carefully selecting vaccine immunogens to target SARS-CoV-2 variants, with particular attention given to the immunogenic relationships among variants. We also evaluated neutralizing antibody kinetics across the three-dose regimen. No measurable neutralizing activity was detected 14 days after DNA priming. Neutralization increased substantially after the first protein boost and reached the highest levels following the second boost, while maintaining a stable breadth profile (Supplementary Fig. 8). This study was conceived within the framework of pandemic preparedness rather than seasonal SARS-CoV-2 circulation. By mapping the antigenic relationships among diverse sarbecoviruses, we aimed to establish a broadly applicable reference for rational immunogen selection.

Cross-neutralization reactivity between trivalent immunized guinea pig sera and 25 sarbecovirus pseudoviruses. a Schematic of the trivalent immunization regimen and blood collection in guinea pigs. The regimen consisted of a priming dose with spike DNA, followed by two booster doses containing spike protein formulated with alum. Sera were collected 14 days after the final immunization. b Neutralization assays of trivalent immunized guinea pig sera against 25 sarbecovirus pseudoviruses. Immunogens are indicated in red. Each dot represents the NT50 value from an individual guinea pig serum sample. The data are presented as the means of three independent experiments. The bars indicate the means ± standard deviations

Leave a Reply