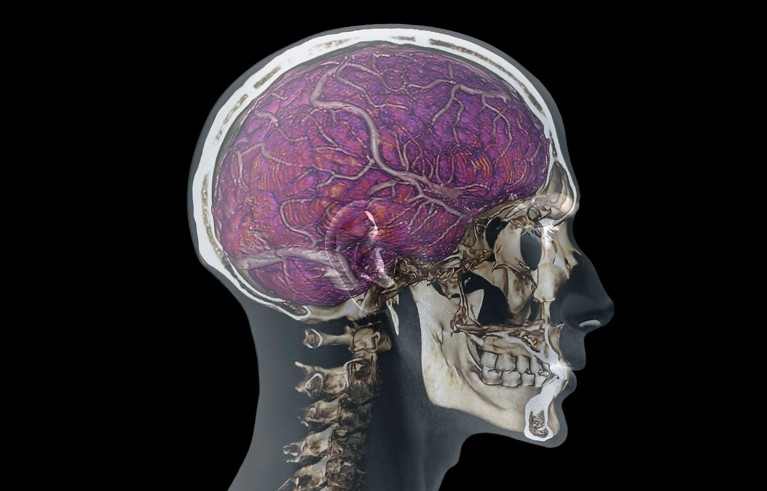

Large veins called the venous sinuses help to drain fluid from the brain and skull.Credit: Zephyr/Science Photo Library

The brain’s sewerage system — a network of large veins embedded in a membrane close to the skull — does not contain passive vessels as it was once thought.

The delicate brain is protected from physical damage and invading pathogens by three layers of membrane called the meninges. Large veins called the venous sinuses, which sit in the outermost membrane, help to drain fluid from the brain and skull, but their full range of activities has been unclear until now. In a study1 in mice and humans published in Nature today, researchers captured the venous sinuses pumping blood and cerebrospinal fluid. The vessels also continuously shuffled their cells around to accommodate for patrolling immune cells.

The study supports the idea that brain borders are highly regulated interfaces rather than simple anatomical coverings, says Jonathan Kipnis, a neuroimmunologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. It is “rigorous and technically sophisticated”, he adds.

The dynamic nature of the venous sinuses is important for protecting the central nervous system, says Dorian McGavern, a neuroimmunologist at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland, and a co-author of the paper. Any build-up of inflammation, fluid or pressure under the skull can quickly endanger the brain, and the sinuses could help to preserve brain function by actively responding to these threats, he says.

Live action

The research team recorded the activity of venous sinuses in live, anaesthetized mice by whittling down a square millimetre of the skull until it was thin enough for a laser to pass through it, illuminating the immune cells, which were labelled with a fluorescent protein, beneath. Using this technique, called intravital imaging, large veins wrapped in smooth muscle could be observed pulsing underneath the skull, constricting and dilating to actively drain fluid.

The researchers created stop-motion videoes of the endothelial cells that make up the vein walls and observed that they contain small holes up to one micrometre in diameter, known as fenestrations, which allow the passage of fluid, molecules and microorganisms. Veins were also able to rearrange their borders to accommodate surveying immune cells. The researchers called this strange behaviour ruffling.

“Having studied vessels now for over 20 years, I’ve never seen a vessel do that before,” says McGavern. “These junctions were opening and closing constantly, and this is basically driven by immune cells that are sniffing around the sinus wall all the time,” he says. “The endothelial cells are pliable in a way that is very, very unique.”

Leave a Reply