Assembly of a large dataset of paired T cell repertoires and HLA allotypes

Given that sample size significantly influences the performance of the imputation models, we assembled a large dataset of paired TCR repertoires and HLA genotypes (Table 1). The TCR repertoires were generated using two TCR-Seq methods, namely, the ImmunoSEQ assay (Adaptive Biotechnologies) and the αβ TCR profiling assay (MiLaboratories), while HLA alleles were imputed from dense SNP genotyping arrays23 (Methods). This enabled us to build, to the best of our knowledge, the largest dataset of paired T cell repertoires with HLA alleles at the time of writing. This dataset included 433 unique HLA alleles from three different populations, namely, Germany, Norway, and the USA. Subsequently, we split the dataset into three parts, first, paired TRB repertoires and HLA alleles (n = 5554 pairs; Fig. 1a), second, paired TRA repertoires and HLA alleles (n = 385 pairs; Fig. 1a). The TCR repertoire of these two subsets was generated using the ImmunoSEQ assay. The third subset contains the TRA repertoires that were profiled using the αβ TCR profiling assay from MiLaboratories with matching HLA alleles (n = 855 pairs; Fig. 1a).

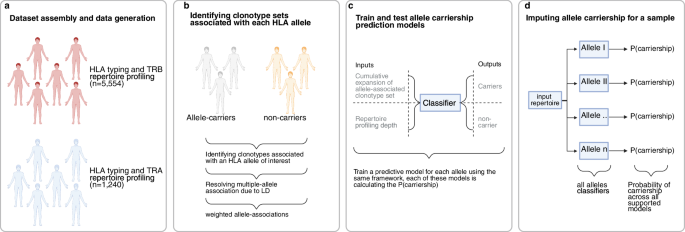

a Shows the cohorts used in the current study to discover TRA- and TRB- clonotypes associated with different HLA alleles. b Summarizes the discovery of clonotypes associated with each allele by comparing their presences in carriers and non-carriers using the Fisher’s exact test followed by resolving linkage-disequilibrium (LD) using L1-regularised linear regression (L1LR)-models. c The machine-learning classifiers developed to predict the carriership of a given HLA allele using the cumulative weighted expansion of clonotypes that are associated with this HLA allele. d The pipeline for imputing HLA alleles from a given TRA or TRB repertoire, where for each of the supported allele-models we calculated the carriership probability. The final HLA-typing for a sample represents alleles with a carriership probability of 0.5 or more. Created in BioRender. ElAbd, H. (2025) https://BioRender.com/2gfo7ks.

Discovering public TRB clonotypes associated with different HLA alleles and developing HLA imputation models based on the TRB repertoire

After splitting the TRB-HLA dataset (n = 5554 pairs) into 80% training and 20% validation we used a similar framework to Zahid et al.13 to build TRB-based HLA imputation models (Methods; Fig. 1). Briefly, we started by discovering clonotypes associated with HLA alleles using the statistical framework described by Emerson et al.10. For each allele, the frequency of public clonotypes in allele carriers relative to non-carriers was compared using a one-sided Fisher’s exact test where clonotypes with an association P-value < 1 × 10−4 are designated as clonotypes associated with the respective HLA allele (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, we used the L1-regularised linear regression model described by Zahid et al.13 to resolve the cases where the same clonotype is associated with multiple HLA alleles due to linkage-disequilibrium (Fig. 1b). Then, we used a weighted sum of the expansion of allele-associated clonotypes as well as the repertoire depth to develop a linear regression model that can distinguish carriers of this allele from non-carriers13 (Fig. 1c). Lastly, each of these allele-models is provided with either the TRA or the TRB repertoire of a given sample to calculate the probability of carrying a given HLA allele (Fig. 1d).

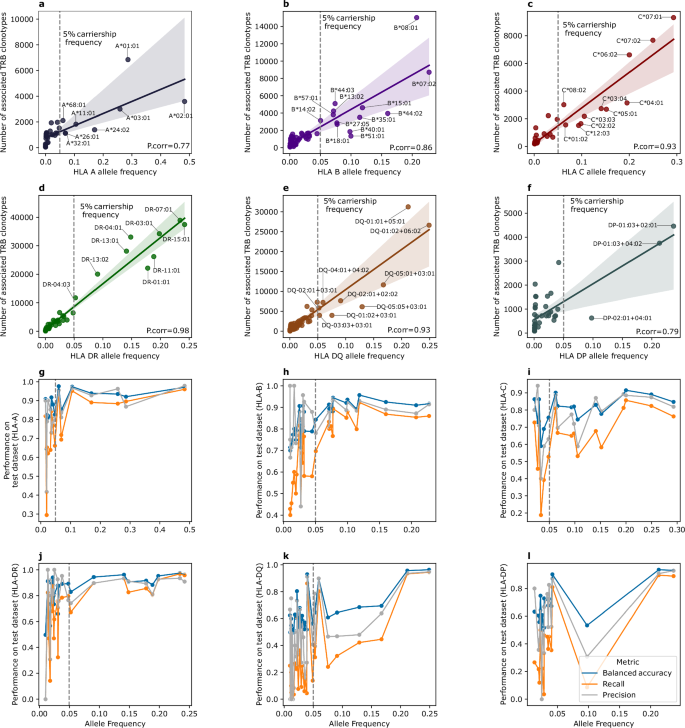

Using 80% of the data, i.e., the training dataset, we identified 722,060 clonotypes that were associated with 312 HLA alleles, with the number of associated clonotypes being a function of allele frequency (Fig. 2a–f). Within the HLA-A locus, only eight alleles had a carriership frequency above 5%, with the most frequent HLA alleles being HLA-A*02:01 with a carriership frequency of ~50% followed by the HLA-A*01:01 (Fig. 2a). Given the higher diversity at the HLA-B locus, there were 13 alleles with a carriership frequency above 5%, with the HLA-B*08:01 and the HLA-B*07:02 being the most frequent and the ones with the highest number of associated clonotypes (Fig. 2b). A similar pattern was observed at the HLA-C locus where only eleven alleles had a carriership frequency >5%, with the HLA-C*07:01, HLA-C*07:02 and HLA-C*06:02 being the most common and, consequently, the alleles with the highest number of associated clonotypes (Fig. 2c). Although the three HLA-I loci showed the same positive correlation between allele frequency and the number of associated clonotypes, the number of associated clonotypes was different among them, with the HLA-B locus having the highest number of associated clonotypes followed by the HLA-A locus and lastly the HLA-C locus (Fig. 2a–c).

The relationship between HLA allele carriership frequency and the number of associated TRB clonotypes for the six classical HLA loci. HLA-A (a), HLA-B (b), HLA-C (c), HLA-DR (d), HLA-DQ (e), HLA-DP (f).“P.corr” denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient. For panel (d), HLA-DR alleles are written in the name of their corresponding HLA-DRB1 alleles because the alpha chain is invariant, hence, DR-07:01 represents the HLA-DR molecules whose beta-chain is encoded by the HLA-DRB1*07:01 allele. For panels (e, f) HLA allele names are written as the alpha chain allele + the beta chain allele, for example, DQ-01:01 + 05:01 represents the HLA molecules encoded by the HLA-DQA1*01:01 and the HLA-DQB1*05:01 alleles. Panels (g–l), the relationship between HLA-allele carriership frequency and the performance of its TRB-based imputation model on a test dataset of 1111 TRB repertoires with linked HLA allotypes. Three performance metrics were used to evaluate the model performance, namely, balanced accuracy, recall and precision. g–i The performance of three HLA-I loci models, namely, HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C, respectively. Similarly, the performance of HLA-II molecules is illustrated in (j–l), with HLA-DR shown in (j), HLA-DQ in (k) and lastly, HLA-DP in (l). The data supporting panels (g–l) are provided in Supplementary data 1.

Within the HLA-II alleles, the HLA-DR locus had the highest number of associated clonotypes, with only nine alleles having a carriership frequency above 5% with the HLA-DRB1*07:01 and HLA-DRB1*15:01 being the two HLA-DR alleles with the highest number of associated clonotypes (Fig. 2d). Within the HLA-DQ molecules, which are generated from the pairing of proteins encoded by the HLA-DQA1 locus and the HLA-DQB1 locus, nine HLA-DQ dimers had a carriership frequency > 5% (Fig. 2e). The most frequent HLA-DQ complex was derived from HLA-DQA1*01:02-DQB1*06:02, followed by the HLA-DQA1*01:01-DQB1*05:01 and the HLA-DQA1*05:01-DQB1*03:01 proteins (Fig. 2e). Only three HLA-DP complexes had a carriership frequency > 5% namely, HLA-DPA1*01:03-DPB1*02:01, followed by HLA-DPA1*01:03-DPB1*04:01 and lastly, HLA-DPA1*02:01-DPB1*04:01 (Fig. 2f).

Most of the clonotypes were restricted to HLA-II alleles (n = 466,277), particularly, HLA-DRB1 (n = 303,330) relative to all HLA-I alleles (n = 145,224), potentially, because of the higher ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells in the blood. These findings also confirm previous reports by DeWitt et al.11, specifically, (i) the strong positive correlation between allele frequency and the number of associated clonotypes, (ii) the higher number of clonotypes that are associated with HLA-II alleles, and (iii) the low number of clonotypes associated with the HLA-C locus. Using the L1-regularized logistic regression framework13, we were able to resolve the association between clonotypes and multiple HLA alleles, however, for a small subset of clonotypes, this was not possible (Methods). Specifically, out of the 600,095 clonotypes that were associated with HLA alleles with a carriership frequency >5%, 587,224 (97.8%) clonotypes were associated with a single HLA allele while only 12,871 (2.2%) clonotypes were associated with multiple alleles.

After building prediction models for these 137 HLA alleles, we tested their performance on the 20% validation dataset (n = 1111 paired TRB-HLA repertoires). Starting with HLA-A alleles, we observed a high performance across most alleles with a median balanced accuracy of 0.88, median precision of 0.85 and a median recall of 0.77 (Supplementary Fig. 1). A similar trend was observed with HLA-B alleles where the median balanced accuracy was 0.87, and the median precision and recall were 0.88 and 0.76, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). The performance of HLA-C allele models was lower than that of HLA-B and HLA-A, with a median balanced accuracy of 0.82, a median precision of 0.79, and a median recall of 0.66 (Supplementary Fig. 3). This might be attributed to the small footprint of HLA-C on the TRB repertoire as it has a lower surface expression24 and a smaller immunopeptidome25.

Regarding HLA-II alleles, HLA-DR alleles illustrated a high performance relative to HLA-DQ and HLA-DP alleles, with a median balanced accuracy of 0.89, a median precision of 0.89, and a median recall of 0.79 (Supplementary Fig. 4). HLA-DQ alleles had an average balanced accuracy of 0.60, an average precision of 0.46, and an average recall of 0.22 (Supplementary Fig. 5). While the average model performance was generally inferior to other HLA proteins discussed so far, some HLA-DQ models showed higher performance. For example, HLA-DQA1*01:02-DQB1*06:02 showed a balanced accuracy of 0.96, precision of 0.94 and a recall of 0.94 (Supplementary Fig. 5). A similar pattern was observed with HLA-DP alleles, where the average balanced accuracy was 0.67 and the average precision and recall were 0.58 and 0.35, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). These performance metrics were mainly driven by a handful of alleles that showed an accurate predictive performance such as the HLA-DPA1*01:03-DPB1*04:02 model, which had a balanced accuracy of 0.93, a precision of 0.92 and a recall of 0.89 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

To investigate factors influencing the performance of these models, we started by analyzing the impact of allele frequency and model performance. For HLA-A alleles we observed a positive correlation between the allele carriership frequency and different performance metrics (Fig. 2g). This relationship was not linear and showed signs of saturation, where carriership frequencies above 0.05-0.1 did not translate into a meaningful increase in the model performance. Similar findings were also observed for HLA-B (Fig. 2h), HLA-C (Fig. 2i) and HLA-DR (Fig. 2j) models. For HLA-DQ (Fig. 2k) and HLA-DP (Fig. 2l), this trend was also observed but to a lesser extent, with some alleles having relatively high carriership frequency ( > 0.1) but a relatively poor performance.

HLA-DQ and HLA-DP proteins are made from two different chains, α and β, leading to the formation of cis and trans proteins. Cis proteins are formed between chains encoded on the same chromosome, while the trans complexes are formed between chains encoded on different chromosomes. For example, an α chain encoded by the paternal copy and a β chain encoded by the maternal copy or vice versa. While the same applies to HLA-DR proteins, the α chain of the HLA-DR molecule is invariant, and hence we focused only on the β chain located either on the paternal or on the maternal chromosome. Several studies have indicated that trans complexes have a minor impact on the formed immunopeptidome26, as not all trans complexes lead to a stable molecule at the cell surface27. This might explain the poor performance of different HLA-DQ and HLA-DP complexes that have a relatively high carriership frequency, as these αβ allele combinations might not generate a stable HLA complex and hence have a minor impact on the TRB repertoire.

To investigate this, we inferred HLA-DQ and HLA-DP haplotype structures statistically (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary data 2 and Supplementary data 3) and compared the performance of cis and trans HLA-DP and HLA-DQ complexes (Supplementary Fig. 8). Most of the alleles with a carriership frequency >1% were potentially cis complexes and we had models for only three trans HLA-DQ complexes, namely, HLA-DQA1*03:01-DQB1*03:03, HLA-DQA1*02:01-DQB1*04:02, and HLA-DQA1*05:05-DQB1*02:02. Similarly, for HLA-DP complexes only one trans-complex had a frequency >1%, specifically, HLA-DPA1*01:03-DPB1*16:01, but all other HLA-DP complexes (n = 15) were potentially cis. Thus, our observations suggest that not all potential cis HLA-DP or HLA-DQ complexes can be accurately imputed from the TRB repertoires.

Motivated by these findings and the performance of the models on the validation dataset, we used the entire dataset for training and developing imputation models using the same workflow introduced above. This enabled us to identify 1,095,576 unique TRB clonotypes that were associated with 437 unique HLA alleles, with 1,049,766 clonotypes showing single-allele association and 45,810 being associated with multiple alleles. After filtering for alleles with a carriership frequency >0.01 (corresponds to n > 55 individuals), we obtained 891,564 clonotypes that were associated with 175 HLA alleles, specifically: 17 HLA-A alleles, 27 HLA-B, 17 HLA-C, 22 HLA-DR, 30 HLA-DP, and 62 HLA-DQ alleles. Consistent with our previous observations, the number of associated clonotypes was higher for HLA-II alleles, particularly HLA-DRB1 alleles, relative to HLA-I alleles. Despite the strong differences between the different HLA loci, within a single locus, allele carriership frequency strongly correlated with the number of associated TRB clonotypes (Supplementary Fig. 9).

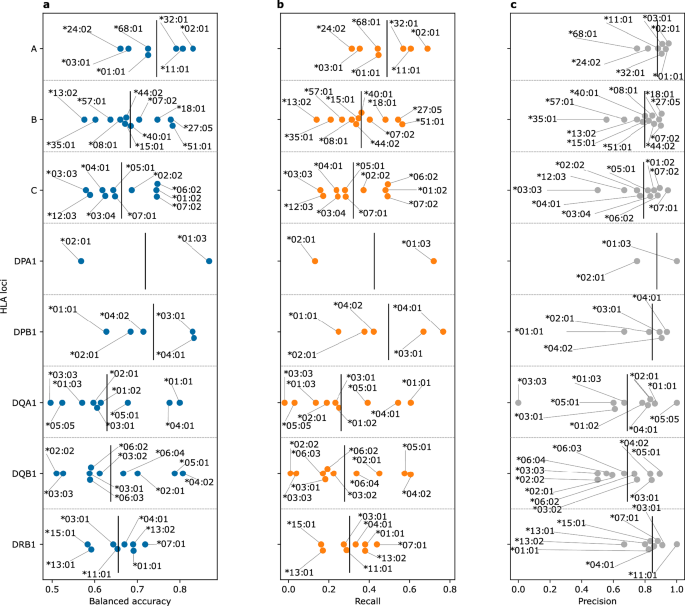

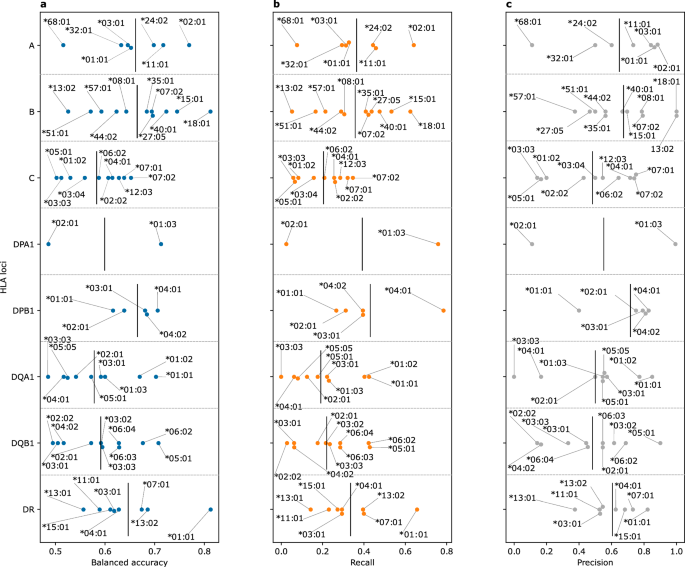

To test the performance of the developed models, we used a previously published dataset28 of 229 healthy and IBD patients with paired HLA allotypes and immune repertoires, where we imputed the HLA of each sample using the TRB repertoire and compared the imputed results to the provided HLA allotypes. Furthermore, we focused the analysis on models with an allele carriership >5% in the training dataset. Although this test dataset was generated with a different TCR-Seq method and from RNA instead of DNA, our developed TRB-models were able to impute common HLA alleles (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 10). Across the different loci, we observed a significant reduction in the recall (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 10), which might be attributed to differences in the TCR-Seq methodology used, as the models were trained on datasets generated via the ImmunoSEQ assay and tested on repertoires profiled using the MiLaboratories assay. The former assay generally enables a deeper repertoire profiling relative to the latter. Hence, this reduction in the profiling depth might explain the reduction in the ability of the models to recall alleles. Nonetheless, the precision of the models remained relatively unchanged (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 10).

a shows the balanced accuracy, while (b) the recall and (c) the precision across different HLA alleles belonging to different HLA loci. Across all panels, alleles with carriership frequency <5% (n < 12 samples) were excluded from the analysis. The data supporting panels (a–c) are provided in Supplementary data 4.

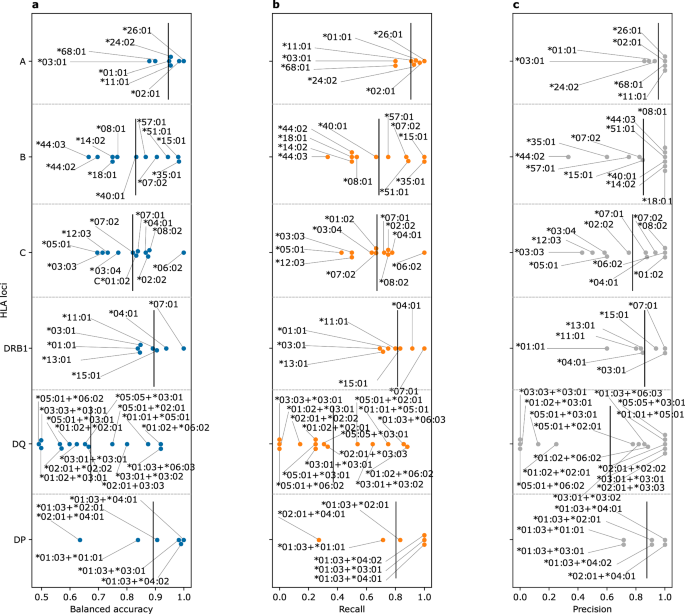

To test the performance of the models on an independent test dataset that was generated with the same technology, i.e., the ImmunoSEQ assay, we used a subset of the immuneCODE29 database with matching HLA allotypes (n = 63 individuals). Subsequently, we imputed the HLA allotypes of each sample from its TRB repertoire using the developed models and compared the imputed alleles to the reported HLA alleles. As seen in Fig. 4, most of the models showed an accurate performance, except for some HLA-DQ complexes (Supplementary Fig. 11). We observed a robust increase in the recall relative to the Rosati et al.28 test dataset. Indicating that the decrease in the recall observed previously can be attributed to the shallow profiling, performed in the Rosati et al.28 study.

a shows the balanced accuracy, while (b) the recall and (c) the precision across different HLA alleles belonging to different HLA loci. Across all panels, alleles with carriership frequency <5% (n < 3 samples) were excluded from the analysis. The data supporting panels (a–c) are provided in Supplementary data 5.

Discovering public TRA clonotypes associated with different HLA allotypes and developing HLA imputation models based on the TRA repertoire

As the TRA repertoire was profiled using two different TCR-Seq technologies, namely, the ImmunoSEQ assay and the αβ TCR profiling assay from MiLaboratories, and using different starting materials, i.e., DNA and RNA, respectively, we did not combine the two datasets and treated each dataset independently. Starting with the dataset made from cohorts HC2, CD3, and UC3 which were profiled using the ImmunoSEQ assay from DNA (Methods), we split the dataset into an 80% training and a 20% validation datasets. We then used the framework described above to discover TRA clonotypes associated with HLA allotypes (Methods). Although our results mirrored those from the TRB repertoires, in which the number of associated clonotypes per HLA allele was strongly dependent on the allele’s carriership frequency (Supplementary Fig. 12), the overall number of TRA-associated clonotypes was lower than the number of TRB-associated clonotypes. This can be attributed to differences in size between the two datasets ( > 5500 TRB repertoires vs. 308 TRA repertoires used for training, i.e., ~ 6% of the TRB dataset), which highlights the impact of the dataset size on discovering clonotypes associated with each allele. Given the small number of repertoires and discovered allele associated-clonotypes, the resulting TRA-based imputation models showed a poor predictive performance, relative to the TRB-models, even for the common HLA alleles, i.e., alleles with carriership frequency >5% (Supplementary Figs. 13– 18).

We repeated the same process with the other TRA-HLA datasets composed of HC3, CD4 and UC4 cohorts, which were profiled using the αβ TCR profiling assay from MiLaboratories with RNA as the starting biological material (Methods). Given that this dataset is ~two-fold the size of the previous TRA-HLA dataset, we observed a higher number of HLA-associated clonotypes, 31,230 relative to 9435 clonotypes. Similar to previous findings, the number of clonotypes associated with each HLA allele positively correlated with the carriership frequency (Supplementary Fig. 19). After testing the models on the 20% validation dataset, we observed a similar trend to the TRB findings where HLA-A (Supplementary Fig. 20) and HLA-B (Supplementary Fig. 21), showed, on average, a higher performance relative to HLA-C (Supplementary Fig. 22) across common HLA alleles (carriership frequency >5%). For common HLA-II alleles, HLA-DR alleles showed the highest performance (Supplementary Fig. 23) relative to HLA-DQ (Supplementary Fig. 24) and HLA-DP (Supplementary Fig. 25). Although the performance of these models was relatively higher than the first TRA-based models trained on the smaller TRA dataset obtained using the ImmunoSEQ assay, it is still inferior to the TRB-based models in terms of the number of supported HLA-alleles and the accuracy of each model.

Consequently, we focused the TRA-based model development on the larger dataset assembled from the HC3, the CD4 and the UC4 cohorts (n = 855 TRA-HLA pairs) where we used the entire dataset to develop imputation models for HLA alleles with a carriership frequency >5%. To test the generalizability of these models we used the independent Rosati et al.28 test dataset (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 26). Relative to TRB-based imputation models, the TRA-models showed an inferior predictive performance, potentially due to the smaller training dataset, 855 TRA-HLA pairs, relative to 5,554 TRB-HLA pairs. Similar to TRB-based models, the TRA-based models suffered from a reduction in the recall relative to precision, potentially due to the shallow repertoire depth of the Rosati et al.28 dataset.

a shows the balanced accuracy, while (b) the recall and (c) the precision across different HLA alleles belonging to different HLA loci. Across all panels, alleles with carriership frequency <5% (n < 12 samples) were excluded from the analysis. The data supporting panels (a–c) are provided in Supplementary data 6.

TCR2HLA achieves a state-of-the-art performance in imputing HLA allotypes from TRB repertoires

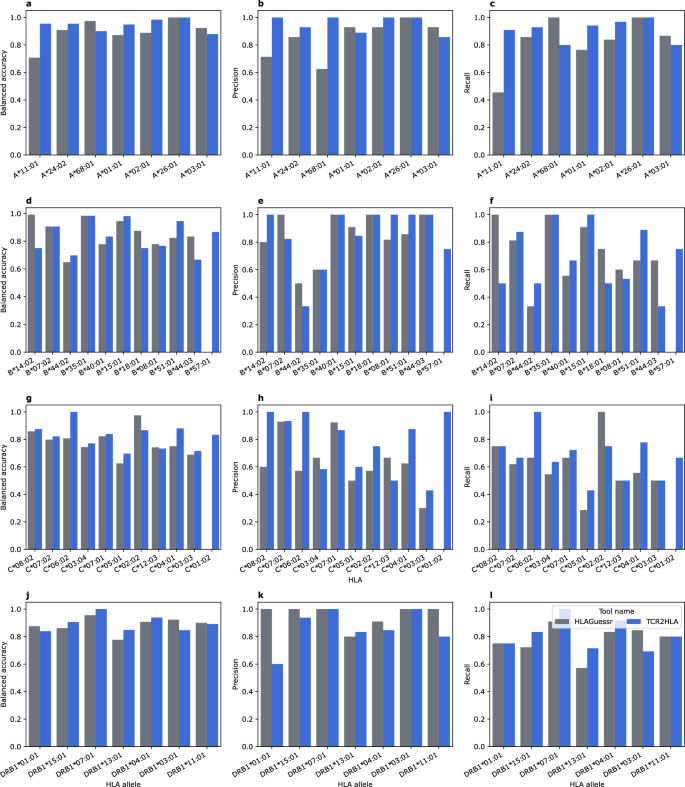

To evaluate the performance of the developed models against other TCR-based imputation pipelines, we benchmarked their predictive performance against HLAGuessr which was recently developed by Ortega et al.12. We focused on analyzing the performance of the TRB models. We selected the immuneCODE datasets29 as it was not included in the training of our tool (TCR2HLA; Code availability) or that of Ortega and colleagues12. Besides the differences in predictive performance (Fig. 6), TCR2HLA offers two advantages over HLAGuessr, first, it can impute functional HLA-DQ and HLA-DP alleles and not just a chain-level prediction, i.e., a specific HLA-DQA or HLA-DQB allele as HLAGuessr does. Second, it supports a larger number of alleles, specifically, 433 alleles, including >175 common HLA alleles, relative to 98 alleles supported by HLAGuessr. As HLAGuessr does not predict functional HLA-DQ and HLA-DP alleles, we restricted the comparisons to the three HLA-I loci and the HLA-DRB1 locus, focusing on common alleles. Across all loci, we observed a comparable performance, where for some alleles the performance of TCR2HLA was better while for others, HLAGuessr yielded a better performance, e.g., HLA-A*11:01 and HLA-A*03:01, respectively (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the tools also differ across metrics, for example, the TCR2HLA model for the HLA-B*14:01 allele showed a higher precision while the HLAGuessr’s model of the same allele showed higher recall and balanced accuracy (Fig. 6). Thus, for common alleles, both tools achieved comparable performance. Consequently, future tools can be developed to combine predictions by both tools to improve the overall imputation accuracy of HLA alleles from TCR repertoire datasets.

a–c The performance of HLA-A models across three metrics, namely, balanced accuracy, precision and recall, respectively. d–f The performance across the three evaluation-metrics for HLA-B models, (g–i) and (j–l) the benchmarking results for HLA-C and HLA-DRB1 models, respectively. The supporting data is available in Supplementary data 7.

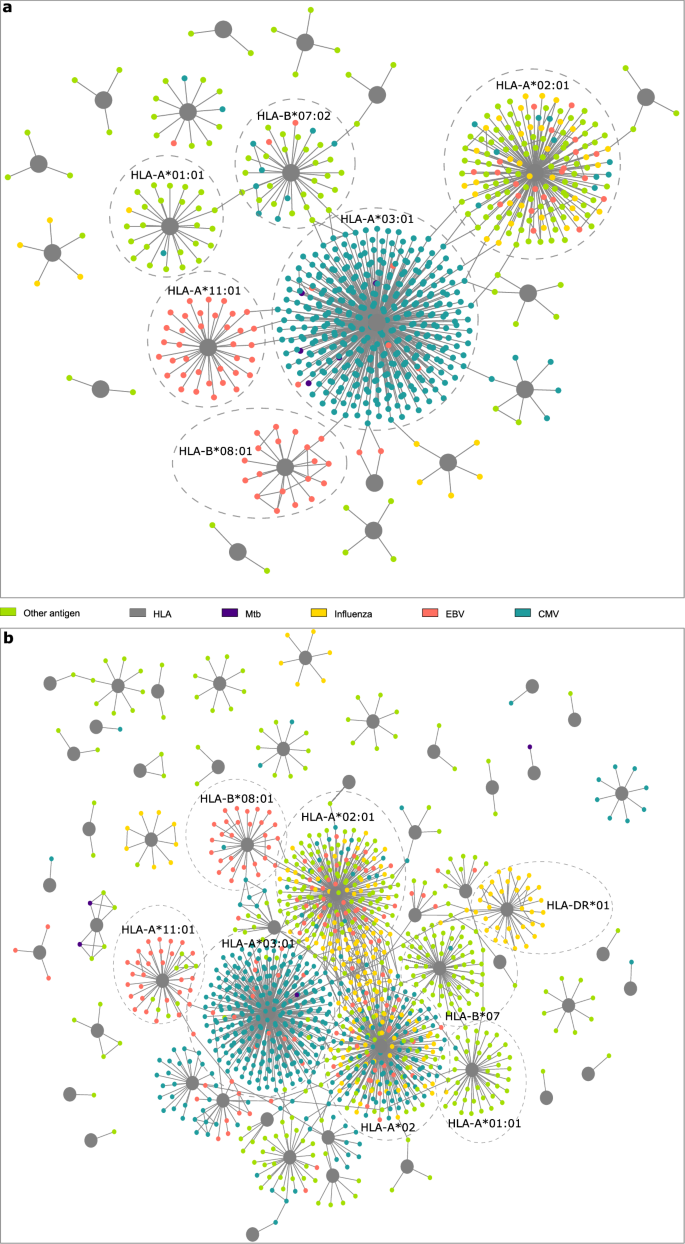

The discovered HLA-associated clonotypes target prevalent infections

To gain more insights into the identified HLA-associated TRA- and TRB- clonotypes, we analyzed their overlap with public TCR-antigen databases, namely, McPAS30 and VDJdb31. From public HLA-restricted TRA clonotypes identified from both TRA-HLA datasets, 1049 clonotypes overlapped with the assembled public database. Most of the identified clonotypes were restricted to common viral and bacterial infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), influenza, and M. tuberculosis, and were specific toward HLA-I proteins with only 16 clonotypes (1.5%) restricted to HLA-II alleles. Most of these 1049 clonotypes were restricted to common HLA-A alleles, such as HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-A*03:01 (Fig. 7a). We could infer the antigenic specificity of only 1910 public HLA-restricted TRB clonotypes that were targeting prevalent infections such as CMV, EBV, and influenza. Furthermore, most of the identified clonotypes were restricted to common HLA-I alleles such as HLA-A*02:01, HLA-A*03:01, HLA-B*08:01 and HLA-B*07:02 (Fig. 7b). By analyzing the sequence of these TRA and TRB clonotypes (Methods; Fig. 7), we did not observe a significant degree of sequence similarity among them, suggesting that the identified clonotypes are recognizing different antigens presented by the same HLA protein.

(a) depicts the overlap between HLA-associated TRA clonotypes and public databases, namely, VDJdb31 and McPAS30 while (b) illustrates the overlap between these databases and HLA-associated TRB clonotypes. Network visualization was performed using Cytoscape57.

Leave a Reply